This is an excerpt from Toronto-based journalist Oren Weisfeld’s new book “The Golden Generation: How Canada Became a Basketball Powerhouse,” which highlights the growth of Canadian basketball from its days of irrelevancy among fans and its reputation as a racially-biased entity.

The 1994 FIBA world championship was originally set to be played in Belgrade, Serbia, until a civil war broke out in Yugoslavia in 1991.

The International Basketball Federation (FIBA) had to reluctantly reopen the bidding competition for a new host. Boris Stankovic, the head of FIBA, called Canadian businessman John Bitove and asked if Canada would consider hosting.

Bitove understood that the only way it would be worth hosting an event of that magnitude was if NBA players were allowed to participate, bringing with them the marketing cache and fan interest that could put butts in seats coming off the heels of the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, Spain.

The Barcelona Games were the first Olympics that allowed professional players to participate in the basketball competition, enabling Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson, Larry Bird and Charles Barkley to come together and form the U.S. Dream Team, dominating the storylines on and off the court. The Dream Team won the gold medal with an average margin of victory of 43.8 points, opening up the world to basketball’s incredible potential.

Book cover for “The Golden Generation: How Canada Became a Basketball Powerhouse” by Oren Weisfeld.

Bitove called NBA commissioner David Stern to ask for his blessing. “(Stern) said, ‘Listen, young man, I don’t know you, but I do know Canada, and I know Toronto,’” Bitove says. “‘And the only way we would allow the pros to play in the world championship is if it’s in North America.’”

With that, a committee co-chaired by Bitove and Canada Basketball CEO Rick Traer raised $13 million and won the bid to host the 11-day tournament held in Toronto’s SkyDome and Maple Leaf Gardens and Hamilton’s Copps Coliseum.

They sold a world championship record 332,334 tickets, including a gold medal game with a record 32,000 fans at the SkyDome. After breaking even on the massive investment weeks before the games began, Canada Basketball got 40 per cent of the profits, which helped keep an organization on the brink of collapse afloat.

One year later, in 1993, Bitove leveraged the contacts he’d made hosting the world championship into becoming the owner of Toronto’s first NBA franchise, the Toronto Raptors. “Without the ’94 worlds,” he says, “I wouldn’t have had the NBA team.”

The 1994 world championship was Steve Nash’s international coming-out party. In his first tournament with Canada’s senior team, a 20-year-old Nash averaged seven points, three assists, three rebounds and two steals in 23 minutes per game as the team’s youngest player. “We spent all of our time trying to get (Canada’s lone NBA player) Rick Fox freed up to play,” Bitove says. “Lo and behold, Steve Nash stole the show.”

Steve Nash drives to the hoop during Canada’s 73-66 world championship loss to Russia on Aug. 7, 1994 at Copps Coliseum in Hamilton.

Despite Nash beginning to capture the country’s attention with his flashy play, the Canadian team disappointed, finishing seventh in the 16-team tournament and second last in their group after losing key games to Russia and Greece. Team USA’s Dream Team II won the tournament behind an MVP performance from Shaquille O’Neal, with its closest margin of victory being a 15-point win over Spain.

“They weren’t good enough to win the worlds that year, but to have at least gone to the finals,” Victoria Times Colonist sports reporter Cleve Dheensaw says. “Canada was eliminated and got a lot of bad press for it, to sit out the quarterfinal stage at home.”

And the bad press didn’t end there. Even though the building was full every time Canada played, it quickly became apparent that most fans were not there to support Canada, but its opponents. In fact, one key game between Canada and Greece saw far more blue flags than red ones, eliciting a rant from Hockey Night in Canada’s Don Cherry.

“Back then basketball was a little bit more of a niche sport,” Nash says. “Fans from those nations were coming out to support the countries against Canada.”

A mix of Canadian and Greek flags fly during a game between Canada and Greece at Copps Coliseum in Hamilton during the 1994 world championship.

It was symbolic of the massive immigrant population in metropolitan cities in Central Canada like Toronto, Montreal and Hamilton in those days, giving testimony to an intense patriotism and basketball fandom that many Canadians could not comprehend. “It was one of the most embarrassing sports events I’ve ever been at,” Doug Smith, a basketball reporter for the Toronto Star, says. “There was no excitement around that, not a lot of buzz about Canada Basketball.”

It wasn’t the first time Canadian basketball players felt a lack of support in their home country, as the sport lacked mainstream appeal prior to the arrival of the Raptors and Vancouver Grizzlies in 1995.

“Nobody ever saw us play,” former Team Canada captain Leo Rautins said.

Jay Triano and Eli Pasquale talked about it all the time. They would walk down the streets of Madrid, Spain, during the 1986 FIBA world championship and people would chant their names and follow them into stores. Meanwhile, in training camp back home in Ottawa weeks prior, the team tried to get into a bar and the bouncer turned them down, not relenting after they explained that they were national team athletes.

“We were better known around the world than we were in our own country,” Triano says.

There would soon be much more pressing concerns for Canada Basketball than the lack of fan interest. Despite having an NBA player in Rick Fox, overseas pros like Greg Wiltjer, Martin Keane, Joey Vickery and Dwight Walton, as well as a young Nash, the team couldn’t compete against the best in the world. And they played a slow, methodical brand of basketball that wasn’t very exciting to watch.

Canada coach Ken Shields watches on during a game against Greece at Copps Coliseum in Hamilton on Aug. 8, 1994.

However, that was what head coach Ken Shields knew, primarily rostering former U Sports athletes who came from the West Coast, including several University of Victoria Vikes — a team he coached to seven straight national championships between 1980 and 1986 that was better known for their fitness and execution than for their speed and skill — and just five Black players. “Let’s be honest: the national teams were white teams,” former Team Canada assistant coach Eddie Pomykala says.

Upon taking over as head coach in 1989, Shields centralized the national team in his hometown of Victoria, using his connections in the city to strike deals with a hotel, apparel company and Thrifty Foods to ensure that a select group of amateur players could train there year-round. “Ken Shields had a program that was unlike anything else in the world,” says Joey Vickery, whose father, Norm, coached Shields in high school. “It was like an experiment. He was like, ‘Guys, I don’t know what this is. But we’re going to be training all year. And maybe one of you might make the team next year.’”

And that experiment paid off, with several of the players improving to the point that they got pro contracts, while four of them even made the Canadian team in 1994.

But it didn’t work for everyone, as the balance of basketball power was shifting from west to east in Canada, specifically toward diverse, metropolitan cities like Toronto and Montreal which were receiving an influx of immigrants from the West Indies. As a result, Toronto- and Montreal-based high school and provincial teams had become dominant, regularly sending athletes to the NCAA and the pros for the first time in the country’s history.

Over 32,000 people watched Team USA beat Russia 137-91 in the world championship final at the SkyDome in 1994.

And because these athletes learned the game by playing pickup on outdoor blacktops in their inner-city neighbourhoods, East Coast ballers played a different brand of basketball that was more individualistic, improvisational, fast, rambunctious, creative, rough and generally played above the rim.

“This city game is quick, it’s upbeat,” John Petrushchak, the legendary coach of the Runnymede Redmen, said. “It comes from street ball. The teams from Metro Toronto are all like that.”

Shields’ teams were not. In fact, Shields dominated Canadian university basketball with an inside-out, John Wooden-inspired offence with two big men stationed in the paint and players meticulously cutting around them in the half court. But when it came to the national team, that style didn’t fully take advantage of the speed, athleticism and instincts of a lot of Canada’s best Black players. In fact, inner-city kids from Toronto and Montreal believed that their chances of making the national team were marginalized because Shields’ system favoured West Coast-based players who practised together for months. And Victoria wasn’t the most friendly or comfortable environment for Black players, either.

“When you grew up in British Columbia, we don’t have a big West Indian community,” Nash says. “We don’t have as much exposure to that culture and community to how they feel about the national team.”

Back then, the organization was also full of traditionalists who only knew one way to play. “They didn’t want the flash,” says Brian Cooper, who was a board member back then and became chair of Canada Basketball in 2020. “They didn’t want the on-court creativity. They didn’t want the iso, one-on-one. They didn’t want any of the celebration.”

It was hard not to wonder if Canada was really putting its best team forward at the 1994 world championship when, less than 10 days after the tournament wrapped up, Canada’s leading newspaper, the Globe and Mail, published a story entitled “Toronto Blacks Assail Basketball Canada.” It claimed that “Basketball Canada has turned its back on … countless other Black basketball players from Toronto.”

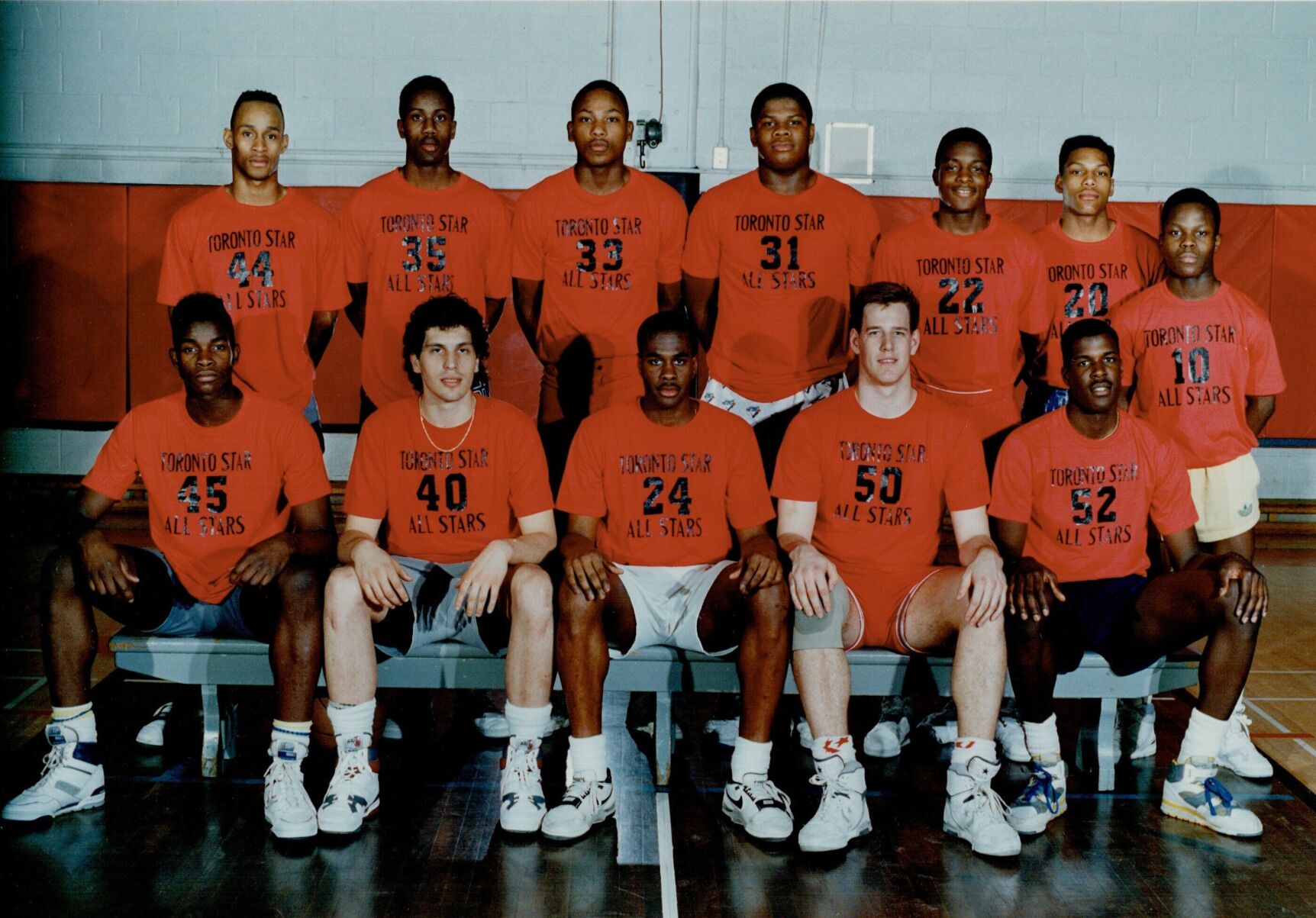

Cordell Llewellyn and Wayne Yearwood were considered two of the best players in the country by the mid ’90s. They developed a reputation as high school stars in Toronto and Montreal, respectively, before going on to play in the NCAA. They even played for Canada at the previous summer’s FIBA Americas tournament before being cut ahead of the ’94 world championship, which they believed was racially motivated.

“They have a preconceived opinion of Black players,” Llewellyn, who averaged 13 points a game at Rhode Island in 1994-95, told the Globe.

Cordell Llewellyn, top left, is part of the Toronto Star all-stars in 1989. Also pictured, clockwise from back row, left, Vinton Bennett, Phillip Dixon, Wayne Robertson, Alan Todd, Clyve Campbell, Jerome Carter, Tony King, Dave Sherwood, Jamie Procope, Roberto Feig, Wayne Simpson.

“They say you’ve got attitude. It’s not my game that got me cut, it’s because they think if you have Canada written across your chest, you have to be white, because to them, Canada’s white, and they’d rather lose than have too many Blacks on the team.”

Yearwood, meanwhile, was a member of Canada’s 1988 Olympic team and had a successful pro career in Greece and Switzerland before rejoining Canada that summer in hopes of landing a new pro contract. He was a veteran leader throughout training camp, helping younger players assimilate to the team. But two weeks before the competition, Shields told Yearwood that he would be an alternate. “I was pissed. And I said to him, ‘You don’t even understand your team,’” Yearwood says. “He didn’t put the best talent on the floor.”

“I think he has a cultural problem, and perceives the Black guys in a different way,” Yearwood told the Globe. “It’s more ignorance than racism. He’s got us typecast. White players are assertive, Black players have attitude. White guys are good players, Black guys are good athletes.”

Freelance journalist Laura Robinson was originally tipped off about the story by an assistant basketball coach at Toronto’s Eastern Commerce Collegiate Institute named Harry Baird, who explained to her that no matter how many stars Toronto sends to NCAA Division I schools, they’re not making the national team. And after interviewing more than 20 players on the record, Robinson concluded that Canada Basketball had a problem of systemic racism stemming from the way it structured its training camps in B.C. and a style of play that favoured West Coast U Sports athletes.

As a result of the Globe story, Canada Basketball sought an external review of its practices conducted by Sport Canada and chaired by Caribbean-Canadian diplomat Cal Best, with Shields saying that if the review found him to be racist, he would step down from the job. After interviewing 60 people inside and outside the organization, the report found that “race played no role in the selection of Canada’s national basketball team,” adding that “No one with whom the committee met, talked to or heard from suggested that racial considerations played any part in selecting and coaching the national team.”

When Oren Weisfeld set out to write about the story of Canada’s national men’s basketball team, he wasn’t sure how many of the sport’s biggest…

When Oren Weisfeld set out to write about the story of Canada’s national men’s basketball team, he wasn’t sure how many of the sport’s biggest…

Shields also sued the Globe and Mail, which settled out of court and issued a retraction in the paper the next day. “The process (allegations of racial prejudice) is not something I’d recommend anyone go through,” Shields said. “The whole thing was very painful.”

However, the 20-page report did make 11 recommendations for the men’s program, including splitting the job of program director and head coach, attracting more minority coaches to participate in the national coaching certification program and expanding the open tryout system to more Canadian cities.

It turned out to be neither the first nor the last allegation of racism made against Canada Basketball. Enabled by a white media cohort and covered up by board members who were out of touch with inner-city communities, it’s a dark side of the country’s basketball history that has never been told. “Nobody speaks about the real issues that existed back then, and nobody has because it’s hard to put yourself out there,” Llewellyn says.

“People of colour, that’s how we get up every morning knowing that you have to be careful with what you say, how you say it, because it’s going to jeopardize — you don’t know who is going to read it.

But it’s also a part of our history. And while the program has changed to the point where there are now Black executives in positions of power and the 12 best players are selected regardless of race or geography, its reputation as a racially biased entity lingered well into the 21st century.

In fact, some of today’s best players grew up with preconceived notions about the national team — ones that set Canada Basketball back decades.