By Lawrence Zhang and Daniel Castro

May 1, 2025

This commentary is a joint publication of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, reflecting the collaborative efforts of both organizations.

Introduction

Canada has a choice to make on artificial intelligence (AI). It can capitalize on its groundbreaking research and top-tier AI talent to remain at the forefront of the global AI economy or risk squandering its early advantage by hesitating at the brink of adoption by focusing on regulation instead of deployment. To maintain its early advantages forged through visionary research, homegrown talent, and strategic investments, Canada will have to focus not only on developing AI but actively deploying it. In an era when AI will enhance everything from crop yields to cancer detection, the central priority should be to accelerate AI adoption to boost Canada’s economic prosperity and quality of life for its citizens, not impose roadblocks to innovation with overly precautionary regulation of this emerging technology.

Countries worldwide now view AI as a strategic tool to boost economic growth rather than a laboratory novelty that requires cautious oversight, deliberately prioritizing the concrete benefits of innovation over speculative safety fears. The United Kingdom has explicitly embraced a pro-innovation stance, avoiding burdensome blanket regulations in favour of flexible, sector-specific guidelines. Similarly, both Republican and Democrat policy-makers in the United States have cautioned against overly strict regulations, arguing that such constraints could prematurely stifle a transformative industry. Following the problematic rollout of its Artificial Intelligence Act and lagging productivity growth due to its suffocating rules for the digital economy, even the EU has ramped up investments in AI commercialization to keep pace with competitors like the US and China.

The global consensus now increasingly favours proactive development and deployment of AI technologies. As US Vice President J.D. Vance remarked at the AI summit in Paris in February 2025, “The AI future will not be won by hand-wringing about safety. It will be won by building.” And regardless of the US administration’s unpopularity in Canada at this point in time, he has a point. If Canada remains overly cautious while its peers advance rapidly, it will be left behind not just in the development of AI but in the multitude of industries where AI will have transformative effects.

Some people fear technological change and advise the government to “handle with care” when dealing with AI because it is “better to be safe than sorry.” But excessive caution will lead to regret as well. The precautionary principle assumes that avoiding hypothetical risks is always the safest path, but in reality, overregulation and stagnation carry their own dangers. Countries that stifle innovation under the guise of safety risk falling behind in economic competitiveness, technological leadership, and even societal well-being. In a rapidly evolving world, being too risk-averse often means ceding progress to those willing to take calculated risks – and that would be the real regret.

Why adoption?

Canada’s early success in AI has earned the country global acclaim. Groundbreaking work in deep learning established world-class research centres in Toronto, Montreal, and Edmonton, culminating in Canada receiving international recognition, including the Nobel Prize in Physics awarded to Geoffrey Hinton in AI research in 2024 and the 2018 Turing Award granted to Yoshua Bengio for his foundational research on deep learning. Canadian universities and incubators have created swaths of AI startups, giving Canada one of the highest concentrations of AI companies globally. Notable ventures like language-model innovator Cohere and AI chipmaker Tenstorrent (that has since redomiciled to the US) have attracted substantial global investment, demonstrating the strength of Canada’s innovation ecosystem, at least for early stage companies. While these achievements provide a strong foundation, success ultimately depends on effectively translating research into practical applications.

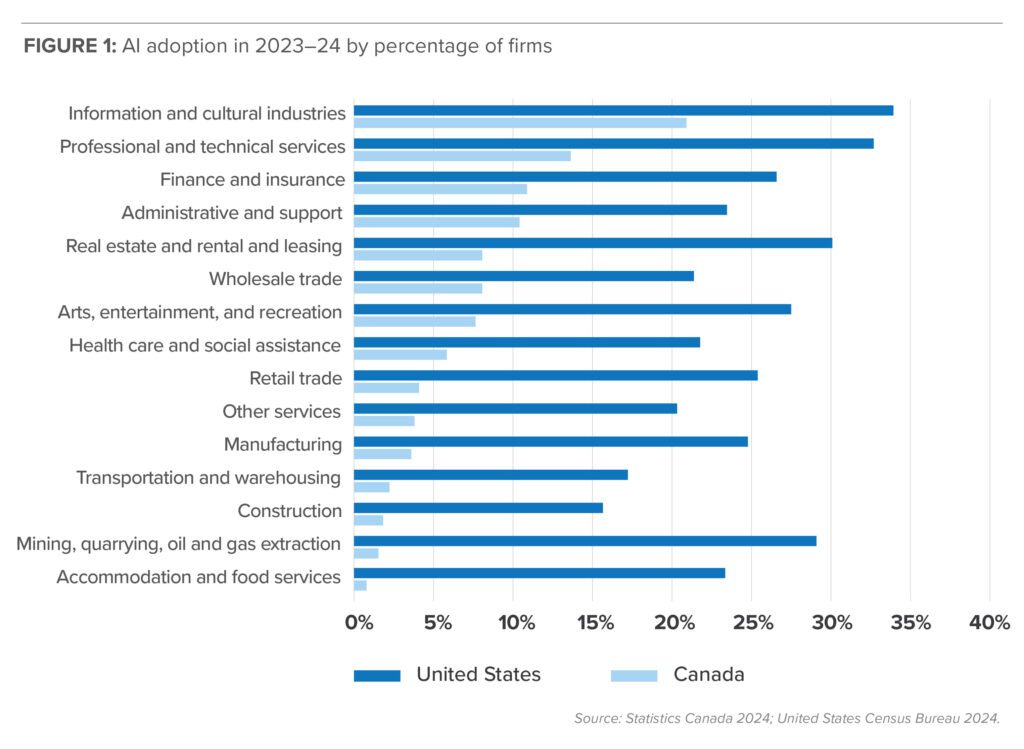

Canada’s Achilles’ heel in AI has been and continues to be adoption. Despite significant research achievements, Canadian firms have struggled to implement AI technologies widely across the economy. One study placed Canada as 20th out of 35 countries for AI adoption among mid-sized and large firms in 2021, with global leaders like Denmark having over double Canada’s adoption rate. Unfortunately, little has changed since 2021, despite the significant attention that both governments and media have placed upon AI in the ensuing years. Data from Statistics Canada and the United States Census Bureau shows that firm-level AI adoption in Canada was less than half of that in the United States in almost every sector save for the information and cultural industries, in which Canadian firms adopted AI at 62 per cent of the rate that their US counterparts did (Figure 1). Even with the explosion in popularity of tools like ChatGPT and Claude AI, three out of four Canadian businesses have not considered adopting generative AI.

Outside of select industries, Canada is not effectively using the technology it helped pioneer compared to some of its peers. In contrast, China, a clear rival in the global AI economy, has developed ambitious policies to accelerate AI adoption throughout key sectors of its economy to drive transformational growth and competitiveness. Without a strategic focus on broad industry adoption, Canada will have borne the full cost of hundreds of millions of dollars in research while allowing most of the economic and productivity benefits to flow to individuals and companies in other parts of the world.

Those who have even casually followed the narrative on Canadian economics at any point in the past twenty years will likely be able to point out that Canada has a productivity problem. Canadian productivity growth has ranked near the bottom of the G7 for the past decade, with an average annual improvement of just 0.9 per cent over the past decade. Nor will it be news that AI offers a lifeline to significantly boost productivity across multiple sectors via labour augmentation and automation, by enabling greater economic output per hour worked. A study from McKinsey & Company estimates that AI could add a staggering $4.4 trillion in annual global productivity potential as its use cases scale. For Canada specifically, one study by Accenture foresees generative AI boosting Canada’s labour productivity by 8 per cent by 2030, equivalent to adding roughly $180 billion to annual GDP. These are enormous opportunities for a country starved of productivity improvements. They imply higher incomes, more competitive industries, and improved public finances if Canada embraces AI.

Less frequently discussed is how domestic AI adoption also drives innovation within Canada. When Canadian businesses across various sectors implement AI solutions, it creates a virtuous cycle: local demand and use cases encourage Canadian entrepreneurs to develop tailored AI tools for specific industries and business functions, which they can then market globally. The current hesitation of Canada’s domestic market to adopt AI, fuelled at least in part by uncertainty over future AI regulations, leads to Canadian AI firms being forced to seek customers abroad even more than they usually would. Canada has witnessed this pattern before – talented individuals and firms generate ideas domestically but commercialize them elsewhere due to limited domestic opportunities – in areas such as biotechnology, software, energy, and defense. Canada should avoid repeating this mistake with AI. Broad domestic adoption will anchor talent and industry within the country and generate continuous innovation as companies gain practical experience. Adoption does not happen passively. It requires a deliberate strategy to elevate Canada from being only an inventor to becoming a global adoption leader.

Skepticism about AI’s immediate economic impact is a common refrain, but risks overlooking the long-term benefits of widespread adoption. A recent report from the Dais noted that AI adoption in Canada has had limited short-term impact on firm productivity, calling for caution in “presuming that business adoption of AI can be a silver bullet in addressing Canada’s productivity growth challenge in the near term.” Despite being a very thorough study, the report looks only at AI adoption between 2019 and 2021, prior to the generative AI (GenAI) boom in late 2022 (for instance, it came before the initial release of ChatGPT, which has served as a major inflection point in AI awareness and usage, reaching 100 million users in only two months).

The Dais report references the Solow paradox, a humorous phrase from the late economist Robert Solow, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” Indeed, history clearly demonstrates that productivity gains from major technologies emerge gradually and that early adopters eventually reap significant advantages once widespread adoption and process adjustments eventually generate substantial efficiency gains. The same pattern held true for the Internet and computers. Modern AI is on a similar path: Although current benefits appear modest, organizations that actively integrate and refine AI processes today will realize substantial future gains once waves of complementary implementation are made through organizational changes, skills development, and internal process redesigns. Thus, businesses that delay adoption until AI technology is “perfected” risk permanently falling behind competitors who embrace early experimentation, and government policy ought to reflect an understanding of this fact.

Past technological revolutions like e-commerce and mobile broadband illustrate the significant advantages of early adoption, with early mover firms and countries reaping the economic and social benefits. Excessive caution in adopting AI will only set Canada further behind, especially when global competitors aren’t slowing down. As seen above, US businesses currently adopt AI at rates more than double those in Canada. If Canadian industries fail to integrate AI promptly, they risk becoming even more uncompetitive on the global stage.

Why not precaution?

Five years after introducing the Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy that sought to boost AI adoption across the economy, the federal Liberal government introduced the (now-defunct) overly precautious Artificial Intelligence and Data Act, largely mimicking the European Union’s similarly overly precautious Artificial Intelligence Act. The passage of this bill would have had a chilling effect on AI adoption across the country, with significant compliance costs and overly stringent rules. To justify the bill, the government provided head-scratching examples of why it is difficult for consumers to trust technology and why action is needed on AI regulation. For example, it cited Amazon’s experimentation with a prototype hiring tool to rate candidates for technical jobs – a tool that penalized women and was subsequently scrapped by the company before it ever saw the light of day because of its problems. Creating a new AI law would not have improved the outcome, and Canada already has stringent laws prohibiting gender discrimination in the workplace.

In the bill, the government proposed covering a far broader swath of AI applications than the European Union law from which it drew inspiration. In fact, the European Union’s law, despite all its shortcomings, took a great deal of care to carve out exceptions for general-purpose AI, scientific research, and applications that pose minimal risk to the public’s health and safety. On the other hand, Canada proposed a completely different classification system that eschewed a risk-based approach and instead placed heavy-handed rules on a broad swath of AI use cases. As a result, AI used to automate parking fees at hospitals would have faced the same level of intensive regulation as AI used in medical devices.

The European Union’s own assessment of its AI law found that complying with the rules could cost a typical small business more than $400,000 for using just one high-risk AI application. Unsurprisingly, raising the cost of developing or using AI also raises the cost of AI itself – making it less accessible and less likely that Canadians will benefit, say, from tools like AI-powered cancer diagnostics, which could help detect illness earlier, or wildfire management systems that could contain the kinds of forest fires that swept through northern Canada in 2023.

This is not to say that AI safety and ethics are not important. Prioritizing AI innovation and adoption over safety is a false dichotomy, and the two are not mutually exclusive. Regulations and legislation should absolutely protect consumers from the harms that AI might cause, though, in the absence of a clear rationale or evidence of tangible harms, a future federal government pondering this question should instead work towards strengthening existing laws like the Employment Equity Act or the Criminal Code to better protect Canadians from bad actors using AI and avoid constraining Canadians’ ability to leverage AI to increase their productivity.

Some may still argue that the government was merely addressing overarching concerns, noting that Canadian firms themselves acknowledge hesitation: 70 per cent express concerns about the ethical implications of AI technologies, and only 21 per cent feel confident in their ability to implement AI tools. Canadians exhibit greater skepticism toward AI benefits compared to other countries, creating barriers related to trust and acceptance. If organizational leaders are wary about AI’s transparency or potential job impacts, adoption slows. While this concern is certainly valid, creating legislation that would hamper the ability of businesses to try out AI tools even in controlled environments would hardly increase firm or individual confidence in the implementation of AI. Past research from the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation shows that the conventional wisdom that regulation of digital technologies increases trust, which in turn increases technology adoption, simply is not true. Beyond some minimum baseline of consumer protection, there is little evidence to suggest that stronger regulation increases consumer trust and adoption. Instead, unnecessarily heavy-handed regulation of digital technologies tends to drain company resources with burdensome compliance costs, negatively impact users, and hurt the startup ecosystem.

To alleviate these concerns, Canada should instead emphasize evidence-based, post-deployment monitoring rather than overly restrictive precautionary measures. Instead of trying to pre-emptively address every potential risk with broad regulations, encouraging widespread AI usage paired with rigorous monitoring by the newly formed Canadian Artificial Intelligence Safety Institute would be an evidence-based means of addressing AI safety. This approach would provide policy-makers with real-world data to pinpoint genuine issues in specific contexts, such as inaccurate credit scoring or AI-enabled cyberattacks, and implement targeted solutions. For example, just as new medications are tested and monitored by Health Canada after market entry, AI systems can be deployed under supervision, evaluated in initial deployments, and adjusted continuously. Developing AI safety technologies and practices in the real world based on actual usage will likely deliver much better results than those built only for a lab and dealing with theoretical worries alone.

Where to focus efforts

Incentivizing and ensuring AI adoption at scale will require overcoming specific barriers that go beyond the usual hurdles of digital adoption. While there are relatively few regulatory, legal, or normative barriers to putting up a company website or moving communications from fax to email, AI adoption may be a different story. However, difficulty should not preclude action.

Based on Figure 1 above, the Canadian information and cultural, professional and technical services, finance and insurance, and the administrative and support industries have been the largest adopters of AI in the past year, while manufacturing; transportation; mining, oil and gas; accommodation, and food services industries have been the slowest to adopt AI. Industries such as real estate, wholesale trade, arts and entertainment, and healthcare fall somewhere in the middle. The information and cultural industries, made up largely of the information technology and media industries, consist of individuals who are largely accustomed to working with digital tools, and generally work in fields in which today’s large language models and machine-learning models can play to their strengths – writing code; generating text, images, and sound; and making data-driven decisions.

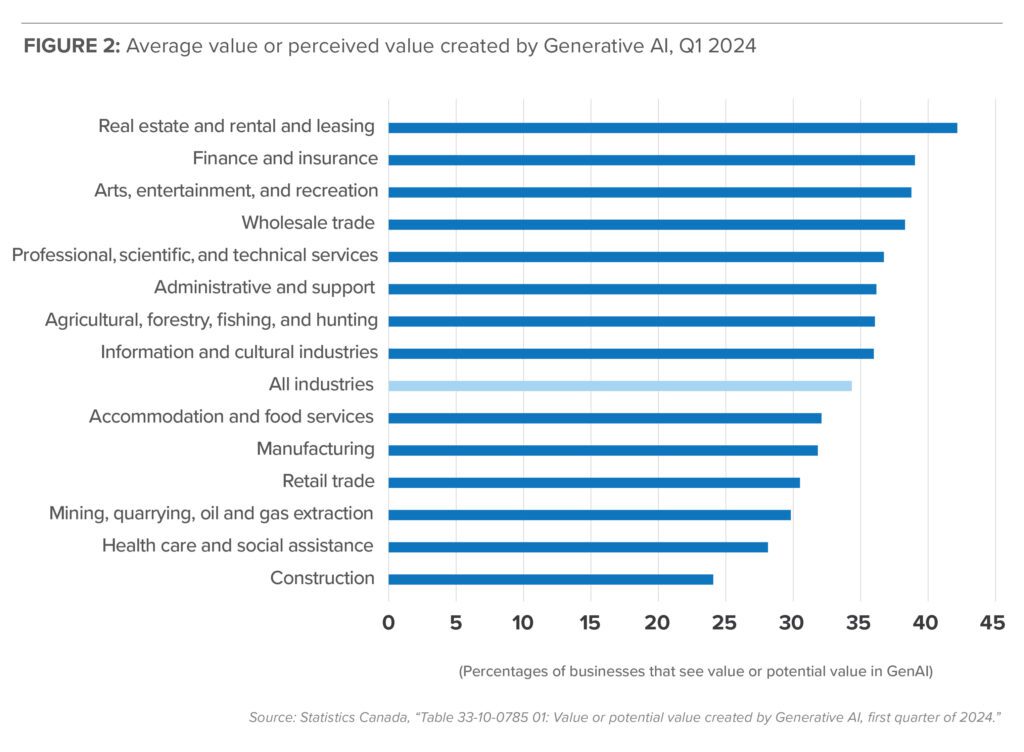

A separate Statistics Canada dataset on GenAI shows a slightly different picture in Figure 2. When ranked by an average of a number of different indicators of value or perceived value of GenAI, sectors such as real estate and rental and leasing, finance and insurance, arts and entertainment, and wholesale trade are among those who see the greatest potential. Professional, scientific and technical services also rank highly. Notably, several sectors that have been slower to adopt broader AI tools – such as real estate and arts and entertainment now see strong potential in GenAI, suggesting untapped opportunities.

Understanding why adoption is slow for specific tasks in certain industries is necessary to improve adoption rates, especially when the barriers to adoption are the result of existing policies. For example, in real estate, there are likely few legal or regulatory barriers to using GenAI to create marketing materials, virtually stage property listings, or schedule in-person showings. That said, there may be laws and policies that hold back the use of AI to write real-estate contracts, negotiate leases with tenants, or dynamically price property rates. Creating clear rules that facilitate AI adoption and do not penalize its use can smooth the pathway for adoption.

The gaps between where AI is being adopted and where generative AI is seen as most valuable point to important opportunities. Some early adopters, like professional services and information industries, may be seeing slower returns from GenAI because they’ve already implemented earlier AI tools. Meanwhile, industries like real estate and entertainment see strong potential in GenAI despite limited prior adoption, suggesting they could leapfrog straight to high-value use cases. Others, including manufacturing and natural resources, may underestimate what GenAI can do. Addressing these gaps with policy reforms, targeted support, real-world pilots, and education initiatives can convert curiosity or doubt into genuine adoption.

These two datasets are not contradictory – they reflect the evolution of AI technology and the growing awareness of new use cases. Traditional white-collar sectors that first adopted AI for analytics, automation, and forecasting are now poised to expand their use into generative applications. Meanwhile, sectors that may not have seen a strong business case for conventional AI tools may find more tangible value in GenAI-enabled solutions for content creation, customer interaction, or property marketing.

A third layer of analysis further refines where adoption is likely to succeed. Occupation-level data from a new study conducted by Anthropic AI show that the occupations most commonly using Claude, a GenAI, are computer and mathematical workers, followed by arts, design, and media occupations, educational roles, and administrative support. This occupational pattern suggests that GenAI adoption is not confined to technical experts and is already spreading into creative and operational roles across a range of industries. As such, workforce skills and job functions should be considered when evaluating where adoption is most feasible and scalable.

Anthropic’s occupational data aligns nicely with sectoral trends: AI uptake is highest in technical and content-heavy roles, many of which cluster in professional and information industries. These industries are likely to lead adoption but also act as sources of diffusion to other industries, as even sectors with low direct AI value perception today, such as construction or oil and gas, employ software developers, analysts, and technical writers. Therefore, gaps may reflect sectoral inertia, not lack of potential, especially since these occupations already embrace AI.

Together, these insights point to a three-part strategy for focusing AI adoption efforts: Industries such as finance, professional services, and administrative support are already implementing AI at scale and stand to benefit from deeper integration of GenAI. These industries may have higher rates of adoption due to fewer legislative, regulatory, or cultural barriers than other industries. Continued support for adoption in these sectors will accelerate productivity and set examples for others.

Meanwhile, industries like real estate, wholesale trade, and arts and entertainment rank AI highly in perceived value but have not yet adopted AI broadly. These industries present ripe opportunities for targeted support that turns said interest into implementation.

Finally, manufacturing, healthcare, transportation, and resource industries have lagged in both AI adoption and enthusiasm. However, applied AI tools such as diagnostic support, patient triage systems, and workflow optimization can deliver real gains. Demonstration projects, investment in building high-quality datasets, and sector-specific guidance can help shift perceptions, chip away at regulatory barriers, and accelerate adoption.

Recommendations

1. Focus adoption-related interventions on industries where AI can deliver the most substantial benefits but where adoption remains sluggish. For example, health care regulators could establish expedited approval processes or regulatory sandboxes for demonstrably low-risk AI solutions. If an AI tool can reliably detect tumors with greater accuracy and far cheaper than current practices, policy-makers should facilitate quicker trials in clinical settings. Health Canada and provincial health agencies could collaborate with innovators on pilot projects involving AI for diagnostics, patient triage, and resource management, thereby generating concrete evidence to support wider implementation. This sandbox strategy, successfully employed in fintech, could effectively be adapted for AI applications. In agriculture, government and industry stakeholders could jointly launch a large-scale Agri-Tech Adoption Initiative that connects farmers with valuable AI-driven tools, such as predictive weather and soil modelling, alongside cost-sharing schemes that encourage trials of these technologies. While the previous Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy focused on adoption, it did so agnostic to sectors and came at a time prior to a widespread consensus on the various use cases of AI.

2. Build data ecosystems to facilitate AI adoption. The availability of high-quality data continues to be a key factor in producing impactful AI systems. As more sectors seek to make use of advances in frontier AI models, they will need to be trained on and have access to relevant datasets. The Canadian government can accelerate AI adoption by investing in the creation and maintenance of high-quality datasets, supporting data sharing across government, industry, and academia, and funding research on privacy-enhancing technologies, such as federated machine learning and homomorphic encryption, to facilitate the use of AI with sensitive data, as well as the development of synthetic data.

3. Across all sectors, expanding skills training will be crucial to address the productivity lag. The government can facilitate this through tax credits or training vouchers for AI skills, particularly targeting SMEs that lack in-house training resources. As workers grow more familiar with AI, adoption will naturally accelerate, driven by internal success stories and peer recommendations. Setting ambitious yet achievable adoption targets, such as ensuring at least half of Canadian businesses integrate AI by 2030, could further concentrate efforts and track progress effectively. Similar goal-oriented strategies have been successful when connecting Canadians to the internet. While each sector will need a tailored roadmap, the overarching principle should be the active promotion of adoption rather than a passive expectation.

4. Canada should avoid creating layers of pre-emptive rules that discourage innovation or drive AI development offshore. Effective regulation should be proportional to actual risks, targeting real harms rather than hypothetical scenarios. Importantly, existing laws addressing clear harms should be rigorously enforced rather than introducing redundant, AI-specific regulations. If an AI-driven system discriminates during hiring, existing human rights and employment equity frameworks are sufficient remedies; discrimination by AI should carry the same penalties as human discrimination. Canada already possesses robust laws addressing fraud, discrimination, and privacy violations, whether caused by human or automated means. Strengthening enforcement of existing regulations is more effective than introducing blanket prohibitions on AI or new regulations for every advancement in AI, such as frontier models or agentic AI. Speculative fears should not hinder innovation.

5. To address safety concerns, Canada should instead emphasize evidence-based, post-deployment monitoring rather than overly restrictive precautionary measures. Rather than attempting to foresee and regulate every conceivable AI risk beforehand, Canada should promote extensive AI deployment, accompanied by careful monitoring from sector-specific regulators, but coordinated through the Canadian Artificial Intelligence Safety Institute, to ensure safety measures are grounded in evidence. This approach would provide policy-makers with real-world data to pinpoint genuine issues like bias or inaccuracies in specific contexts and implement targeted solutions. For example, just as new medications are tested and monitored by Health Canada after market entry, AI systems can be deployed under supervision, evaluated while in use, and adjusted continuously. Practical safety measures based on real-world deployments will outperform those developed for theoretical safety concerns time and time again.

6. Government leadership through public sector AI adoption is critical. Visible endorsement and practical application by policy-makers send a powerful message. The federal government should keep its mandate requiring all departments and agencies to consider AI when adopting new initiatives. However, the current mandate appears to be on track to allow change-resistant government bodies to simply say “no thanks” to AI adoption. Public sector AI adoption builds public trust and visibly demonstrate AI’s practical benefits through tangible improvements, like faster passport processing or reduced hospital wait times. Furthermore, active use of AI by governments compels necessary updates to procurement policies, data-sharing standards, and privacy protections, aligning regulations with technological advancements. By actively using AI, Canadian public institutions can set benchmarks, mitigate public skepticism through transparency, and stimulate domestic AI industries through government contracts. Rather than observing from the sidelines, Canadian governments of all orders must actively engage with AI technology to build an economy of the future.

Canada’s economic future depends on actually using AI, not just inventing it or supporting AI startups. Despite the country’s early breakthroughs and global recognition, adoption has lagged. Getting businesses to use AI won’t happen through vague or one-size-fits-all policies. Different industries will need tailored approaches. Financial and professional services firms, which already use AI heavily, need support scaling their efforts. Industries like real estate or entertainment, interested but cautious, would benefit most from hands-on pilot projects to demonstrate value. Even sectors traditionally slow to adopt new technologies, like manufacturing, health care, or natural resources, can be nudged forward with targeted incentives and identifying regulatory barriers. Canada still has an opportunity to capitalize on its early AI lead, but policy-makers must shift focus from precaution and theory to practical strategies designed specifically around each industry’s unique hurdles and opportunities.

About the authors

Lawrence Zhang is head of policy for the Centre for Canadian Innovation and Competitiveness at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF). He leads research and policy analysis on how Canada can drive economic growth through innovation, technology adoption, and industrial strategy.

Daniel Castro is vice president at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation and director of ITIF’s Center for Data Innovation. Castro writes and speaks on a variety of issues related to information technology and internet policy, including privacy, security, intellectual property, Internet governance, e-government, and accessibility for people with disabilities.